Overview

At one level, evolution is remarkably simple, with just a few concepts – mutation, recombination, random drift and natural selection – that underlie the overall process. Yet this description obscures many issues that make evolution a fascinating area for study. Evolution typically involves many genes and often revolves around interactions between individuals and their environments. Moreover, genes interact with one another and with the environment in a nonlinear fashion, resulting in complex phenotypes and evolutionary dynamics. Our work aims to describe and analyze such interactions with experimental and quantitative rigour. Specifically work in my lab aims to address the fundamental question about the mechanistic basis of observed phenotypic variation. That is, how genetic (and environmental) variation modulate developmental processes and ultimately influence phenotypic outcomes. Our research employs genetic and genomic approaches to address these issues, largely using Drosophila (fruit flies) as a model system. Most labs that work with Drosophila study either individual mutations of large effect (such as those that completely knock out a particular function) or subtle quantitative variation (rarely identifying specific genes). We employ both of these empirical approaches in conjunction with our genomic analyses to help relate our understanding from developmental genetics with the natural variation observed in populations. In the sections that follow, I summarize our findings and future directions for several projects conducted in my laboratory.

How does natural variation in cell size influence mutational robustness and evolvability for complex morphologies

Functional genetic and genomic approaches for the analyses of conditional effects of mutations

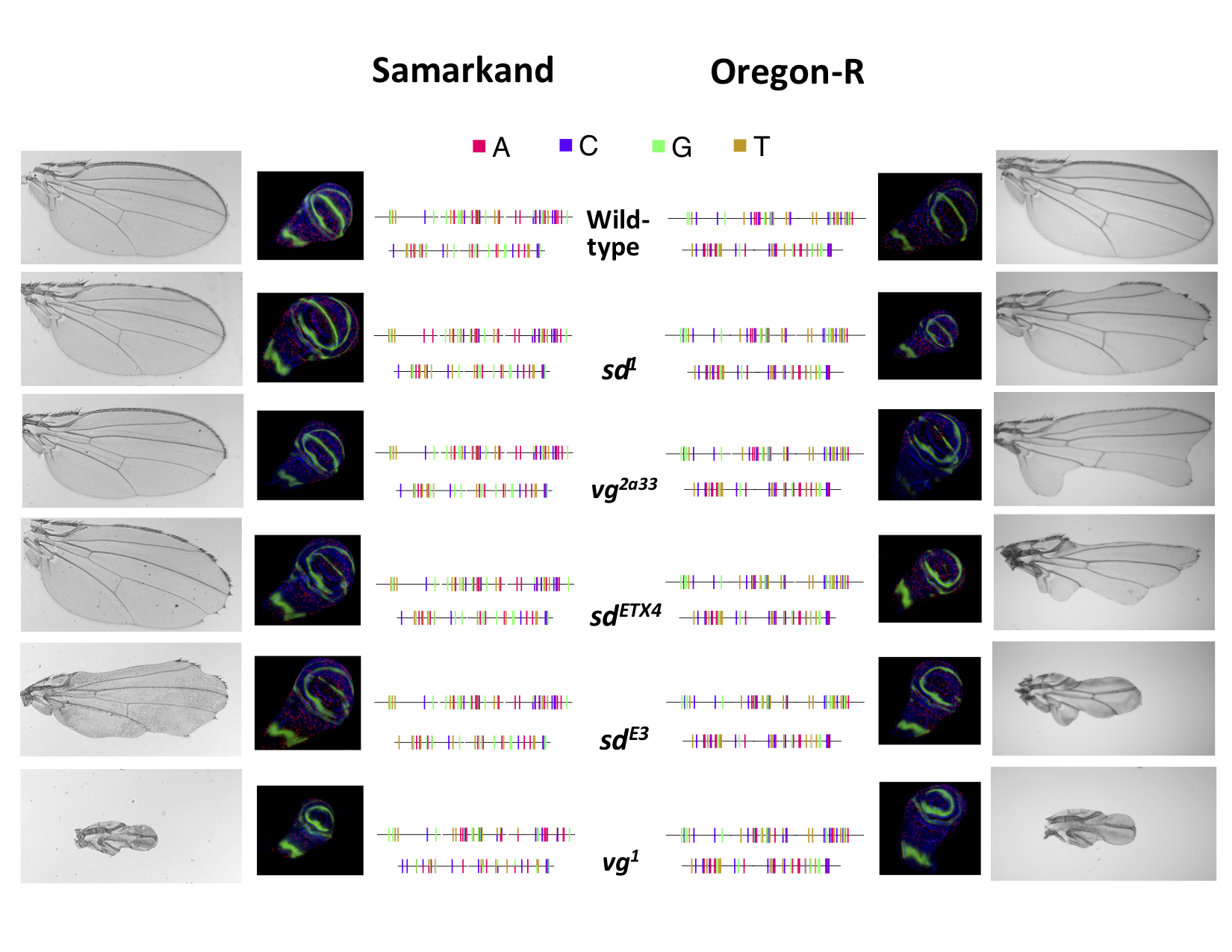

The consequences of any mutation depend both on the genomic context in which it occurs and the organism’s environment. It is well known that not all wild-type genetic backgrounds are “equal”, and large effects mutations can vary in their impact on phenotypes (phenotypic expressivity) due to genetic background. Yet, little is known about the functional consequences of such genetic background effects. Utilizing functionally characterized mutations, we study the impact of wild-type genetic background and rearing environment on the phenotypic expression of these alleles. In particular this work treats the degree of phenotypic effect of a mutation (expressivity) as a quantitative trait subject to many genetic and environmental influences.

We characterize the joint influences of genetic background and the environmental on many “genetic characteristics” such as the ordering of mutational effects (allelic series), intra-genic (complementation) interactions, as well as inter-genic (epistasis) interactions. We are investigating these effects using a number of genes and phenotypes (developmental, morphological and behavioural). Previously we demonstrated (Dworkin et al. 2009) that the genetic interaction between mutations in two genes were background dependent. We extended this work to a genomic scale, and have demonstrated that ~ 74% of all genetic interactions with this system are background dependent (Chari and Dworkin, 2013). We have recently completed a comprehensive analysis of this context dependence for several genes, using a range of mutations varying in severity (Chandler, Chari et al. 2017). This work demonstrates that the ordering of allelic effects is not severely affected, despite background effects on individual mutations. We have also generated and integrated numerous genomic level data sets (genomic resequencing, RNAseq, transcription factor binding predictions) to aid us in identifying the genetic variants responsible for the background dependence of our mutant alleles, as well as to aid in our ability to further understand the consequences of such effects (Chandler et al. 2014). Recent work in the lab has examined a set of mutations (both individual effects and their epistatic impacts in combination) varying in phenotypic effects across a number of genes influencing the development and morphology of the Drosophila wing. This work is forthcoming (look for preprints in 2024 and 2025).

Complementary to the studies described above, we are also “inverting the problem” by asking the question “What are the characteristics of variation in natural populations generating these conditional effects?” (Ledón-Rettig et al. 2015). In particular we ask 1) what is the role of standing genetic variation for compensating for the effects of deleterious developmental mutations , and 2) How does evolution result in a “re-wiring” of the developmental genetic network for the target (optimal) phenotypes. Using experimental evolution and artificial selection to compensate for the phenotypic and fitness effects of deleterious mutations, we have demonstrated segregating variation that can compensate for the phenotypic effects of these mutations. Yet, natural selection recovers the deleterious fitness effects in an independent manner, likely due to antagonistic pleiotropy (Chari et al. In revision, Chandler et al. 2020). We are also genetically and developmentally characterizing these populations (via resequencing of both the genomes and transcriptomes). Further to this, we are now addressing why cryptic genetic variants are segregating in natural populations. By recreating the classic genetic assimilation experiment by C.H. Waddington, and using genomic analyses and fitness assays we aim to identify genetic variants that contribute to the response, and assess if (and how) these alleles contribute to variation in fitness in natural populations (Marzec et al. in revision).

Dissecting the genetic architecture of wing shape in Drosophila.

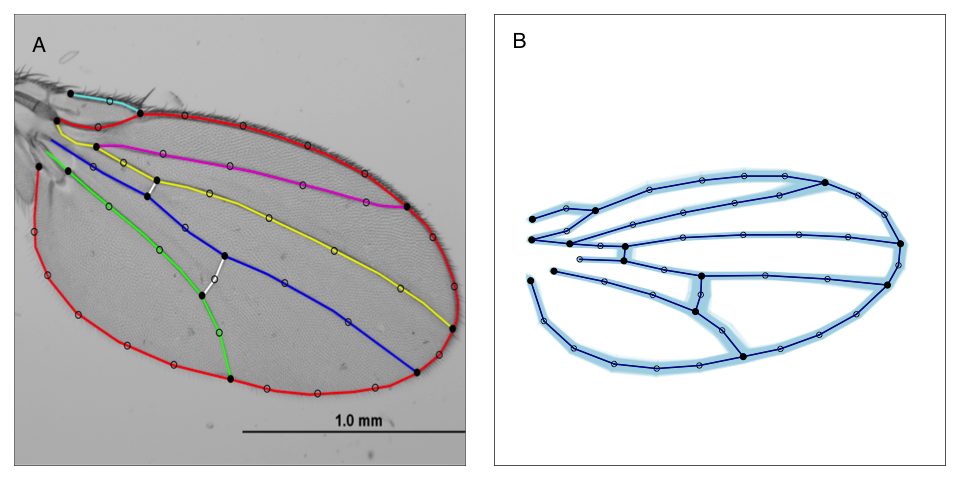

One of the goals of evolutionary genetics is to elucidate the genetic architecture that underlies complex phenotypes. Yet most work in the field still focuses on identifying variants that contribute to trait variation, without considering the proximate mechanism by which they achieve their effect. On the other hand, to be able to developmentally dissect the functional basis of genetic variants that modulate subtle phenotypic changes, requires a model system that can be accurately and sensitively quantified. Drosophila Wing shape represents an ideal model system to study questions about genetic architecture from both an evolutionary and functional perspective.

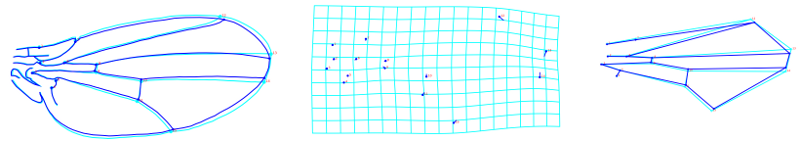

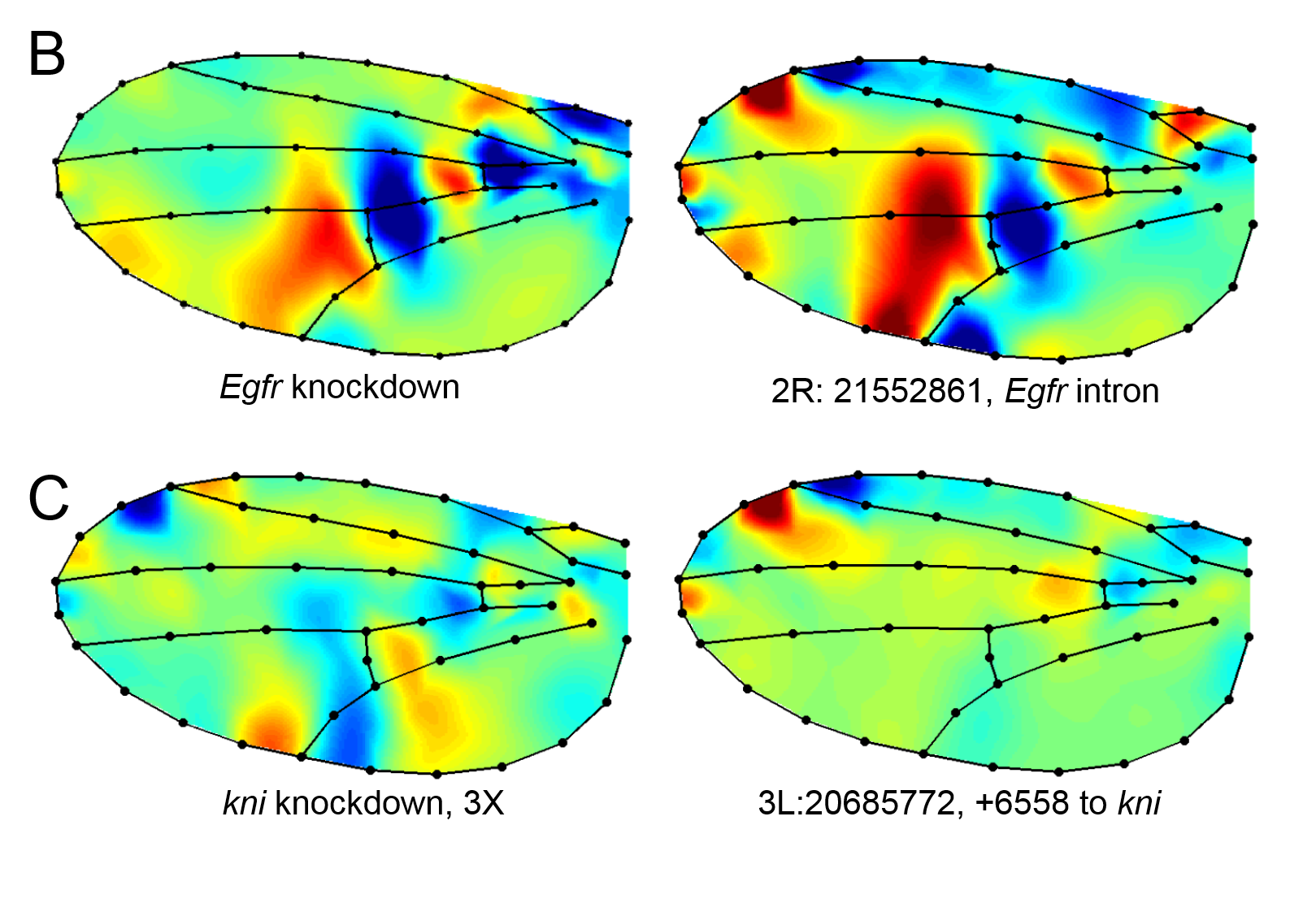

Wing shape is a complex multivariate phenotype, yet it is sufficiently straightforward to measure that we can perform large high throughput experiments in Drosophila. Using a 58 dimensional representation of wing shape to assess variation for wing shape we utilize a combination of induced mutations (Sonnenschein et al. 2015, Testa and Dworkin 2016, Haber and Dworkin 2017), controlled environmental variation, and natural genetic variation (Pitchers et al. 2013, Pitchers et al. 2019, Pesevski and Dworkin 2020) to address our questions. For instance, we utilize induced mutations in highly controlled genetic backgrounds, to help elucidate the proximate mechanisms that shape trait expression as well as plasticity of genetic effects (i.e. Debat et al 2009; Haber and Dworkin 2017) and the relationship between subtle genetic perturbations on wing shape and how it co-varies with gene expression (Dworkin et al. 2011). Using these approaches we are now focused on understanding sex-limited effects of mutations on size and shape, and how these contribute to sexual dimorphism (Testa and Dworkin 2016).

In our work to identify and functionally characterize how naturally segregating polymorphisms influence wing shape we keep our central question (how do such variants influence development which in turn mediate shape change?). For instance, we examined natural variation for the cis-regulatory (enhancer) of the cut gene, known to influence wing development. Variation in the enhancer is present as two alternative haplotypes differing in expression of cut, which we verified transgenically. While the differences in gene expression are substantial, the effects on wing shape are subtle.

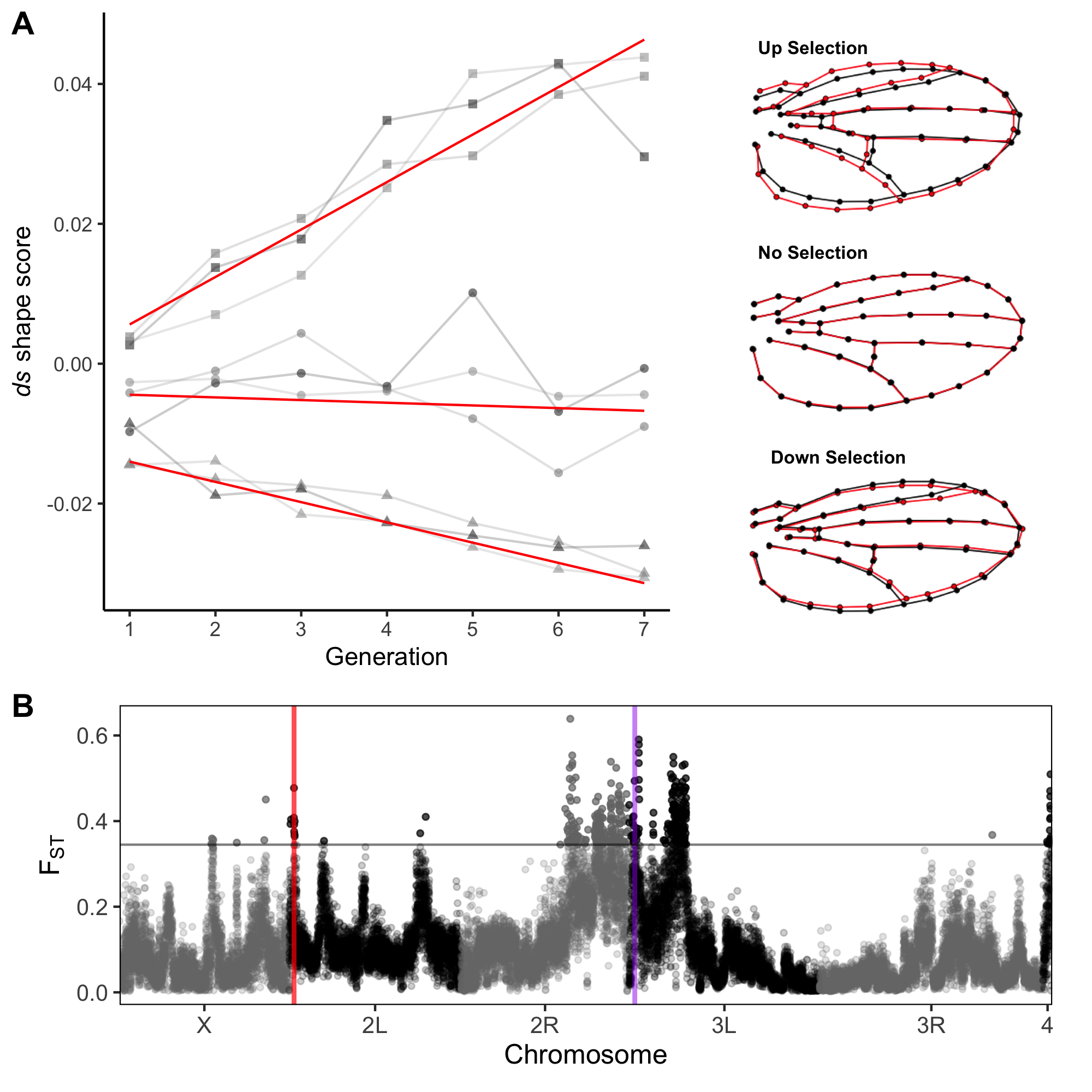

In addition to this work, we are taking a broad genomics approach. Using a panel of Drosophila strains (derived from natural populations) that have been completely resequenced, we have performed genome-wide association mapping (GWAS) for wing shape. This has enabled us to identify alleles that contribute to wing shape. In collaboration with Dr. David Houle (Florida State University), we have used these findings as a resource to aid in the development of a model of wing development, and combining these with “evolve and resequence” approaches to verify the effects (Pitchers et al. 2019, Pelletier et al. 2023).

Sexual selection, and the evolution of sexual dimorphism

Evolution of sexual size and shape dimorphism in Drosophila melanogaster

Evolutionary Genomics of condition dependent sexual size dimorphism in the Drosophila rhopoloa clade

Evolutionary genomics of social behaviour

For a number of years we have collaborated with the lab of Dr. Reuven Dukas, in the Department of Psychology, Neuroscience and Behaviour, on the study of natural, segregating variation influencing social behaviours, in particular social aggregation, in Drosophila.

older work (we don’t really work on this any more)

Evolution of anti-predator behaviour and morphology

Before you read, how about some cool short videos of some of behaviours!!!

Drosophila retreating (reverse walking) away from a mantid predator

Drosophila doing an abdominal lifting/bobbing behaviour when under predation risk. We still don’t know the function (if any) of this behaviour!

Evolution of anti-predation traits: Experimental Evolution using Drosophila. How do organisms evolve in response to a novel predator, and how is this evolutionary response mediated by interactions among different types of traits (such as behavior and morphology)? To address this, we have a research program that seeks to understand the evolution of anti-predation phenotypes (morphological and behavioural) using Drosophila as model “prey” system (Parigi et al. 2019). While researchers have examined the role of predators as agents of natural selection, few have examined the long term (inter-generational) consequences. Conversely, while Drosophila has a rich history for studies of selection, only a few have provided an ecological context. In our lab we previously initiated experimental evolution studies where Drosophila is under pressure of predation by preying mantids (Tenodera aridifolia sinensis), or jumping spiders (Salticus scenicus). Initial work has demonstrated selection on wing size and shape, and we are currently exploring how multivariate selection has changed during 100 generations of selection. In addition we have examined the evolved populations for potential trade-offs for other traits (Elliot et al. 2015, Elliot et al. 2017).